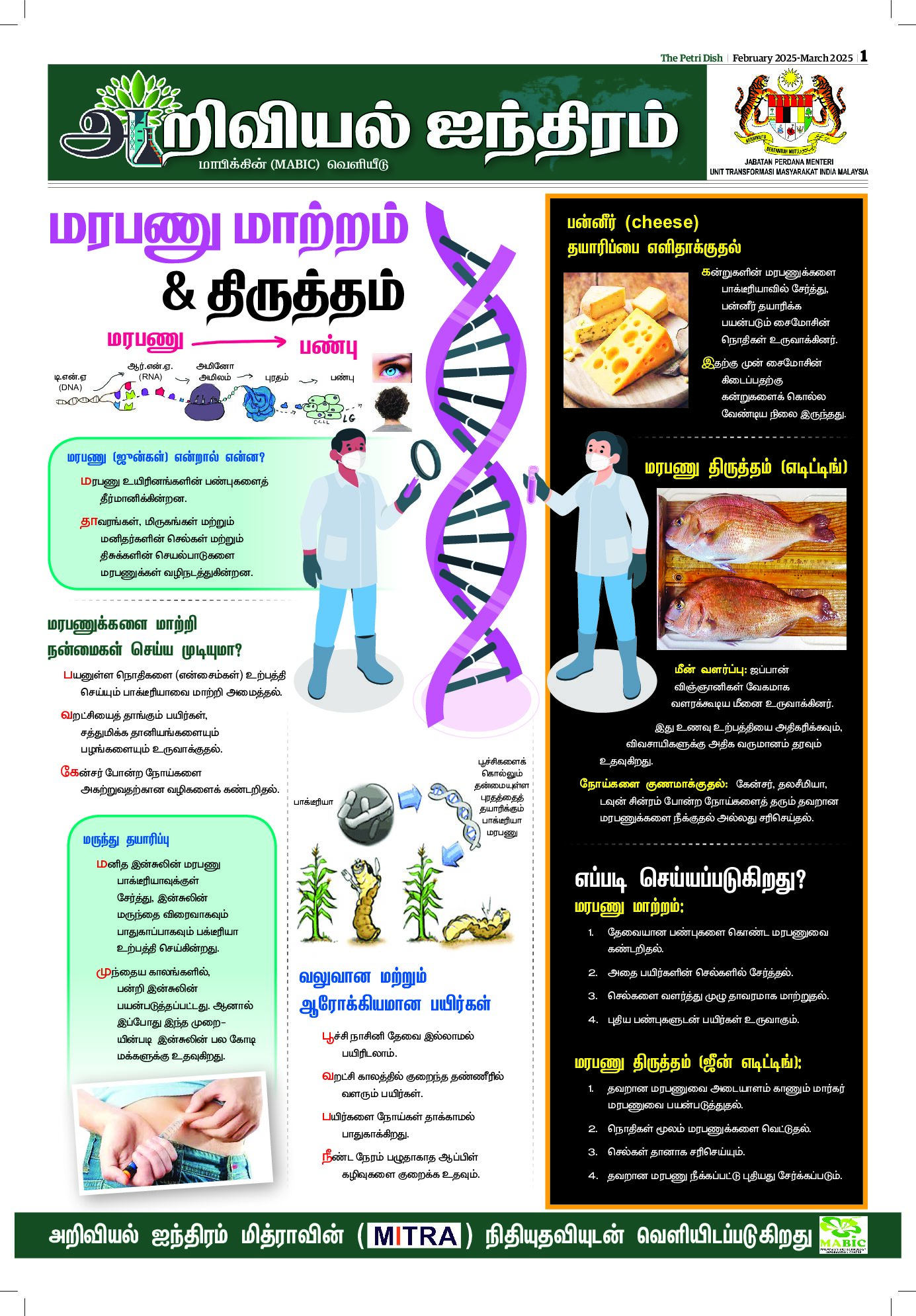

UNIVERSITY of Sussex mathematician, Dr Konstantin Blyuss, working with biologists at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, has developed a chemical-free way to precisely target a parasitic worm that destroys wheat crops.

This breakthrough method of pest control works with the plant’s own genes to kill specific microscopic worms, called nematodes, without harming any other insects, birds or mammals.

Dr Konstantin Blyuss, from the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences at the University of Sussex, said:

“With a rising global population needing to be fed, and an urgent need to switch from fossil fuels to biofuels, our research is an important step forward in the search for environmentally safe crop protection which doesn’t harm bees or other insects.”

An estimated $130 billion worth of crops are lost every year to diseases caused by nematodes. Targeting the harmful nematodes with chemical pesticides is problematic because they can indiscriminately harm other insects.

There are naturally occurring bacteria contained in soil which can help protect plants against harmful nematodes, but until now there has not been an effective way to harness the power of these bacteria to protect crops on a large scale.

Dr Blyuss and his colleagues have used ‘RNA interference’ (RNAi) to precisely target a species of nematode that harms wheat.

Dr Blyuss explained: “A nematode, as all other living organisms, requires some proteins to be produced to survive and make offspring, and RNA interference is a process which stops, or silences, production of these.”

The team has developed a method to ‘silence’ the harmful nematode’s genes by using biostimulants derived from naturally occurring soil bacteria. The biostimulants also ‘switch off’ the plant’s own genes that are affected by the nematodes, making it much harder for the parasite to harm the crop.

The gene silencing process is triggered when biostimulants, which are metabolites of bacteria occurring naturally in the soil, are applied to wheat. The biostimulants can be applied either by soaking the seeds or roots in a solution containing the biostimulants, or by adding the solution to the soil in which the plants are growing.

Though still early, Sablani envisions working with the food industry to integrate his sensor into a milk bottle’s plastic cap so consumers can easily see how much longer the product will stay fresh. – University of Sussex