BY DR TAN MIN MIN

“DON’T hold your baby too much. If not, you’ll spoil her, and she’ll be clingy.”

When my first girl was a few months old, there was a non-parent 60 plus year-old lady in my church who would bug me every week with this advice.

“She is just a baby. If I don’t carry her, should I put her on the floor?” I asked. “You should put her in a stroller, not carry her all the time!”

Ever since I became a mother five years ago, I have been advised not to carry my baby too much. Recently I delivered my second baby, and she would cry when I put her down. My firstborn, who is now five years old, asked me, ‘Mommy, why does a baby want to be carried all the time?’

So, I told her about Harry Harlow’s experiments with baby rhesus monkeys in the 1950s.

Harry Harlow (1905-1981) was an American psychologist who conducted a series of experiments on rhesus monkeys to study maternal-child attachment and social isolation.

At that time the prevailing belief was that emotions were non-existent among babies; they did not love their mothers, they only needed their mother for feeding. Psychologists admonished parents to withhold affection from their children to prevent them from developing mental problems in adulthood.

Harlow’s venture into the study of affection was revolutionary – there was a disdain for the study of motherly love among psychologists during the first half of the 20th century.

To prepare for his experiments, Harlow and his team of graduate students separated baby monkeys from their mothers 6 to 12 hours after birth. He observed that “a baby monkey raised on a bare wire-mesh cage floor survives with difficulty, if at all, during the first five days of life. If a wire-mesh cone is introduced, the baby does better; and, if the cone is covered with terry cloth, husky, healthy, happy babies evolve.”

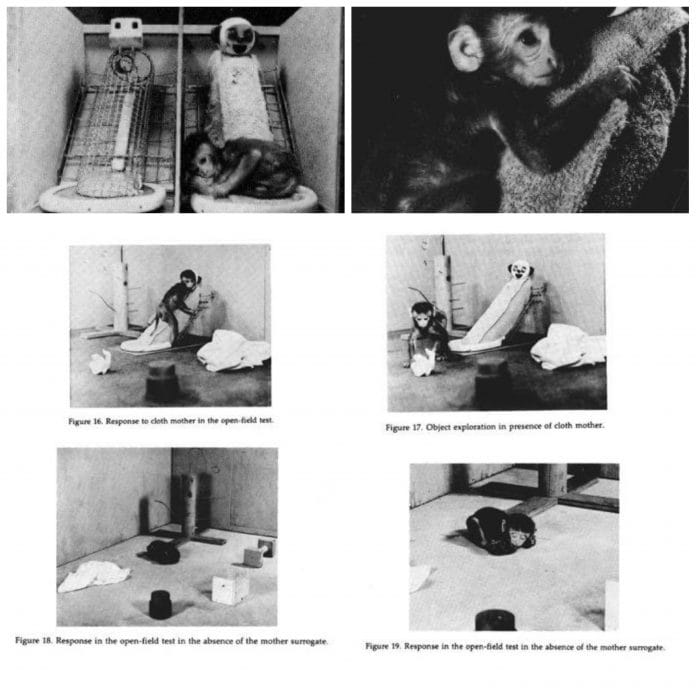

Harlow introduced baby monkeys to two surrogate mothers, one was bare wire, another was covered with terry cloth. Both were warmed by a light bulb. In one experimental condition, the baby monkeys were presented with a wire mother that was equipped with a milk bottle and a cloth mother that wasn’t; in the other condition, the wire mother did not provide milk while the cloth mother did.

If a mother provides comfort but no food, will the baby monkey still cling to it? If the mother-infant relationship is based solely on food, then the baby monkeys would spend more time with the wire mother with milk.

Baby monkeys who had a ‘lactating’ mother clinged to her most of the time, as expected. Meanwhile, in the other condition, the baby monkey would feed from the wire mother quickly when hungry and went back to the cloth mother. Over time, the baby monkeys spent more and more time with the cloth mother and less and less time with the wire mother. By the age of 20-25 days, both groups of baby monkeys spent about the same amount of time with the soft, comforting cloth mother. When the baby monkeys were exposed to a toy bear to elicit fear, they would seek the cloth mother whether she provided milk or not.

In open-field tests, the baby monkeys were introduced to a new environment where there were new objects scattered around. When the surrogate mother was present in the centre of the room, a baby monkey would cling to her, explore the new objects, return to the mother before going on exploring again. When the mother was absent, the monkey would rush to the center of the room where the mother had been placed, run around the room from object to object, screaming and crying. It would crouch in fear and suck its thumb. The presence of a wire mother did not soothe the baby monkey.

Harlow’s experiments reveal the importance of carer’s love for healthy child development. His results were contrary to the belief that a mother’s main function was to provide food. “It takes more than a baby and a box to make a normal monkey,” reported Haslow in his seminal paper The Nature of Love.

‘These data make it obvious that contact comfort is a variable of overwhelming importance in the development of affectional response, whereas lactation is a variable of negligible importance,’ added Harlow in his paper.

By today’s standards, Harlow’s experiments were unethical. Ironically, the cruel experiments helped pave the way to curb cruel child-rearing practices prevalent in many homes, nurseries, and orphanages. Hospitalism describes the adverse effects of long term institutional care on children. During Harlow’s time, children in foundling homes (institutions for abandoned children) who were left alone with minimal touch often developed psychiatric disturbances subsequently, while those placed in foster care were more likely to grow up happily and healthily.

Traditionally women are assigned the role of caregiving. Another revolutionary implication of Harlow’s experiments is that men could also be the main carers and provide comfort to infants.

‘We now know that women in the working classes are not needed in the home because of their primary mammalian capabilities; and it is possible that in the foreseeable future neonatal nursing will not be regarded as a necessity, but as a luxury —to use Veblen’s term — a form of conspicuous consumption limited perhaps to the upper classes. But whatever course history may take, it is comforting to know that we are now in contact with the nature of love,’ concluded Harlow in his paper.

NOTE: Connect with Min Min on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook (@drminmintan) or LinkedIn.