The number of hungry people in the world has increased since 2015, reversing years of progress.

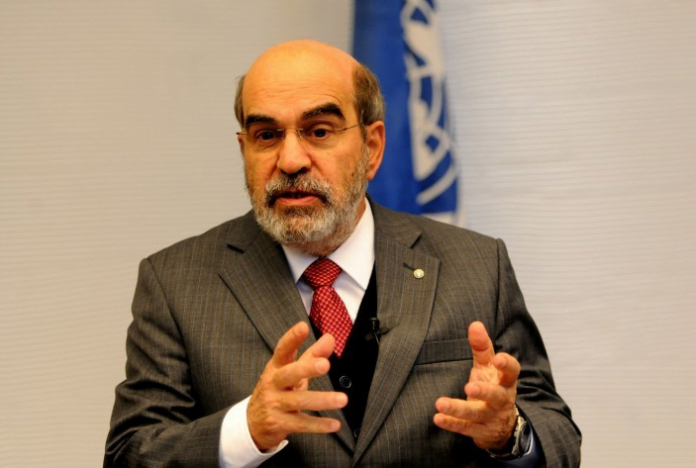

The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) Director-General José Graziano da Silva told member states recently at the opening of the agency’s biennial conference.

Graziano da Silva stressed that almost 60 per cent of the people suffering from hunger in the world live in countries affected by conflict and climate change.

FAO currently identifies 19 countries in a protracted crisis situation, often also facing extreme climatic events such as droughts and floods.

FAO has signalled high risk of famine in northeast Nige-ria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen with 20 million people severely affected.

The livelihoods of these mostly rural people have been disrupted and “many of them have found no option other than increasing the statistics of distress migration,” da Silva said.

“Strong political commitment to eradicate hunger is fundamental, but it is not enough,” he said.

“Hunger will only be defeated if countries translate their pledges into action, especially at national and local levels.”

“Peace is of course the key to ending these crises, but we cannot wait for peace to take action” and FAO, the World Food Programme and the International Fund for Agricultural Development are all working hard to assist vulnerable people, he said.

“It is extremely important to ensure that these people have the conditions to continue producing their own food.

Vulnerable rural people cannot be left behind, especially youth and women.”

He addressed the FAO Conference (July 3-8), the organisation’s highest governing body which reviews and votes on the programme of work and budget and discusses priority areas related to food and agriculture.

Some 1,100 participants will attend the meeting, including one head of state, one prime minister, 82 ministers and numerous representatives from international organisations, the private sector and civil society.

FAO’s top priorities for the next two years include promoting sustainable agriculture, climate change mitigation and adaptation, poverty reduction, water scarcity, migration and the support of conflict-affected rural livelihoods as well as ongoing work on nutrition, fisheries, forestry and Antimicrobial Resistance.

The prospect of the worst food crisis since the Second World War – affecting northeastern Nigerian, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen – means “we mustn’t be resigned but make renewed and extraordinary efforts,” said Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni delivering the keynote speech.

He described the UN’s Zero Hunger objective as a way to achieve peace, justice and equality and preserve the world for the future.

Gentiloni appealed to all of Europe to share Italy’s burden of large-scale arrivals in his country, in order to be “faithful to its own history, principles and civilisation.”

But development efforts must go beyond responding to emergencies, he said.

“We cannot save people by putting them in camps,” insisted da Silva.

“To save lives, we have to save their livelihoods.”

Pope Francis expressed strong support for FAO’s agenda, emphasising the need for solidarity and recognition of human rights.

“We are all conscious that the intention to assure all their daily bread is not enough – it is imperative that we recognise that everyone has the right to food,” the pontiff said in remarks delivered by Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s Secretary of State.