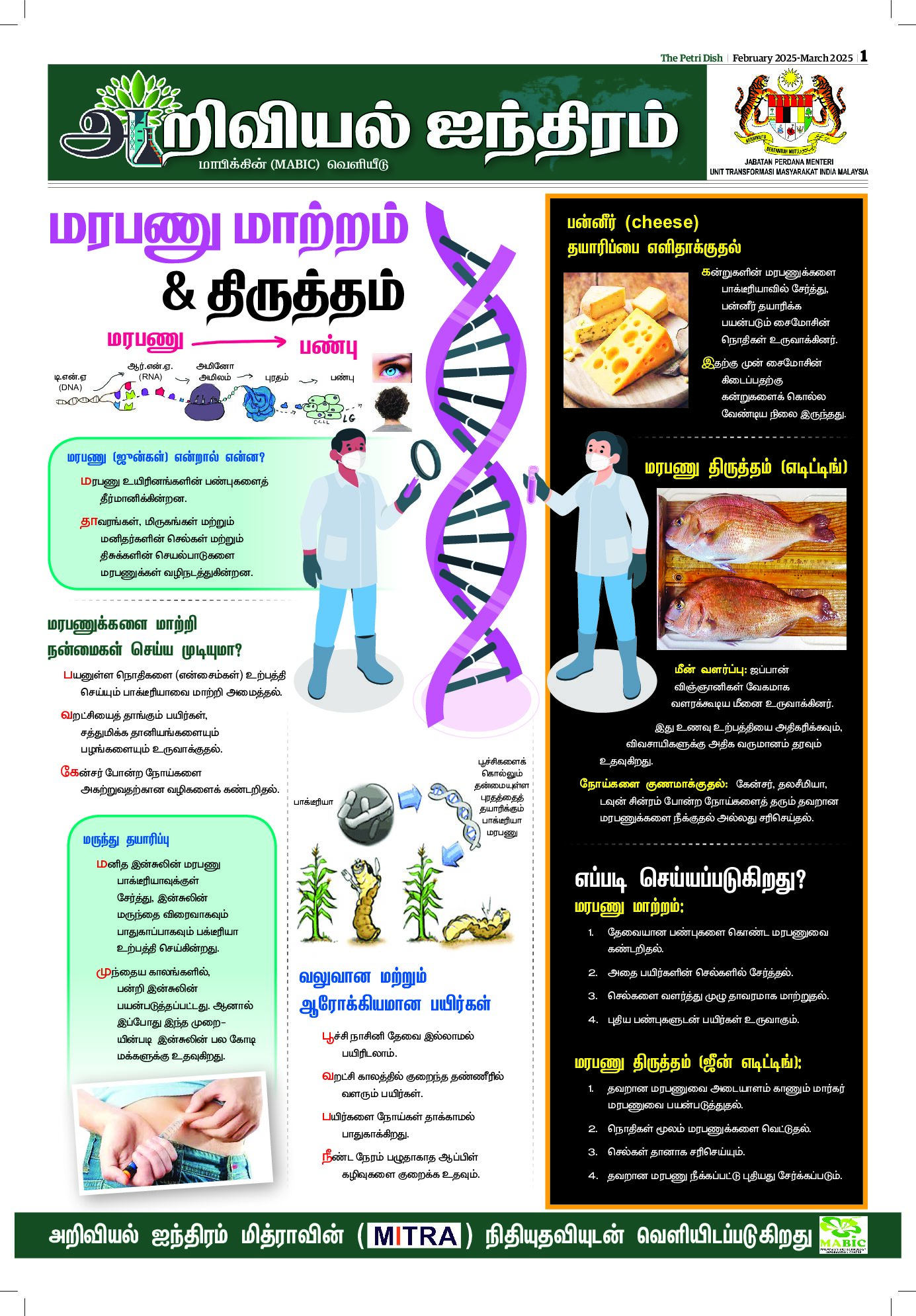

THE 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is creating a viral archive, an archaeological record of history in the making. One aspect of this archive is increased environmental pollution, not least through discarded face-masks and gloves, collectively known as PPE, that characterise the pandemic.

These items of plastic waste have become symbolic of the pandemic and have now entered the archaeological record, in particular face-masks.

In the UK alone, 748 million items of PPE, amounting to 14 million items a day, were delivered to hospitals in the two or so months from 25 February 2020, comprising 360 million gloves, 158 million masks, 135 million aprons and one million gowns.

Within the context of this COVID-specific, single-use plastic and its impacts, the authors of the study argue that an archaeological perspective is uniquely placed to inform a policy-informed approach to tackling environmental pollution.

According to the study, pollution created by the COVID-19 pandemic presents a crisis that would benefit from ‘crisis thinking’, where the aim is to define the social conditions that enable crises to be identified and for suitable action to be taken.

In particular, archaeology can contribute to much-needed solutions with its focus on the prevalence and resilience of a material culture.

The study, which is published in the journal Antiquity, involved the University of York, the University of Sunshine Coast and the University of Tasmania.

Commenting on his co-author Dr Kathy Townsend of University of the Sunshine Coast (Australia) finding a discarded face mask in the stomach of a dead Green sea turtle off Australia’s Queensland coast, Professor John Schofield from the University of York’s Department of Archaeology, said: “As archaeologists, we emphasise the fact human actions have created this problem, both in general terms and here, in this specific case. Somebody wore this face mask, and then discarded it”.

“Understanding human behaviours through the material culture they leave behind is what archaeologists do, whether in prehistory, the medieval period, or yesterday. We think that this object-centred approach provides a distinct and helpful perspective on the problem of environmental pollution.”

“Our study speaks to the wider issues exposed by the pandemic, demonstrating one of the ways that archaeology remains relevant and useful in shaping sustainable futures.”

The authors say that archaeology has previously proved helpful in studying pandemics.

Prof Schofield added: “Our approach is less concerned with the archaeological evidence for pandemics in the past, or even the present, but more about what an archaeological lens adds to our understanding of the current and ongoing pandemic and its longer-term implications.”

The authors cite the scientific research on plastic pollution on the Galapagos islands, and how community action and assistance from non-governmental organisations, have influenced the islands’ Governing Council to change its plastic pollution policies. This includes the implementation of a waste management programme that has the highest recycling rate in Ecuador.

According to Joanna Vince, Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the University of Tasmania: “Archaeologists need to be more involved in the public debate on plastic pollution in order to inform policy decisions further. The first step is for archaeologists to increase their collaboration with policy specialists, government decision-makers and industry.”

Estelle Praet, PhD student at York and co-author of the paper added “The face-mask, as material culture that became almost simultaneously symbolic worldwide, allowed us to reflect upon this building archaeological record through a multi-disciplinary perspective.”