BY STEVEN CERIER

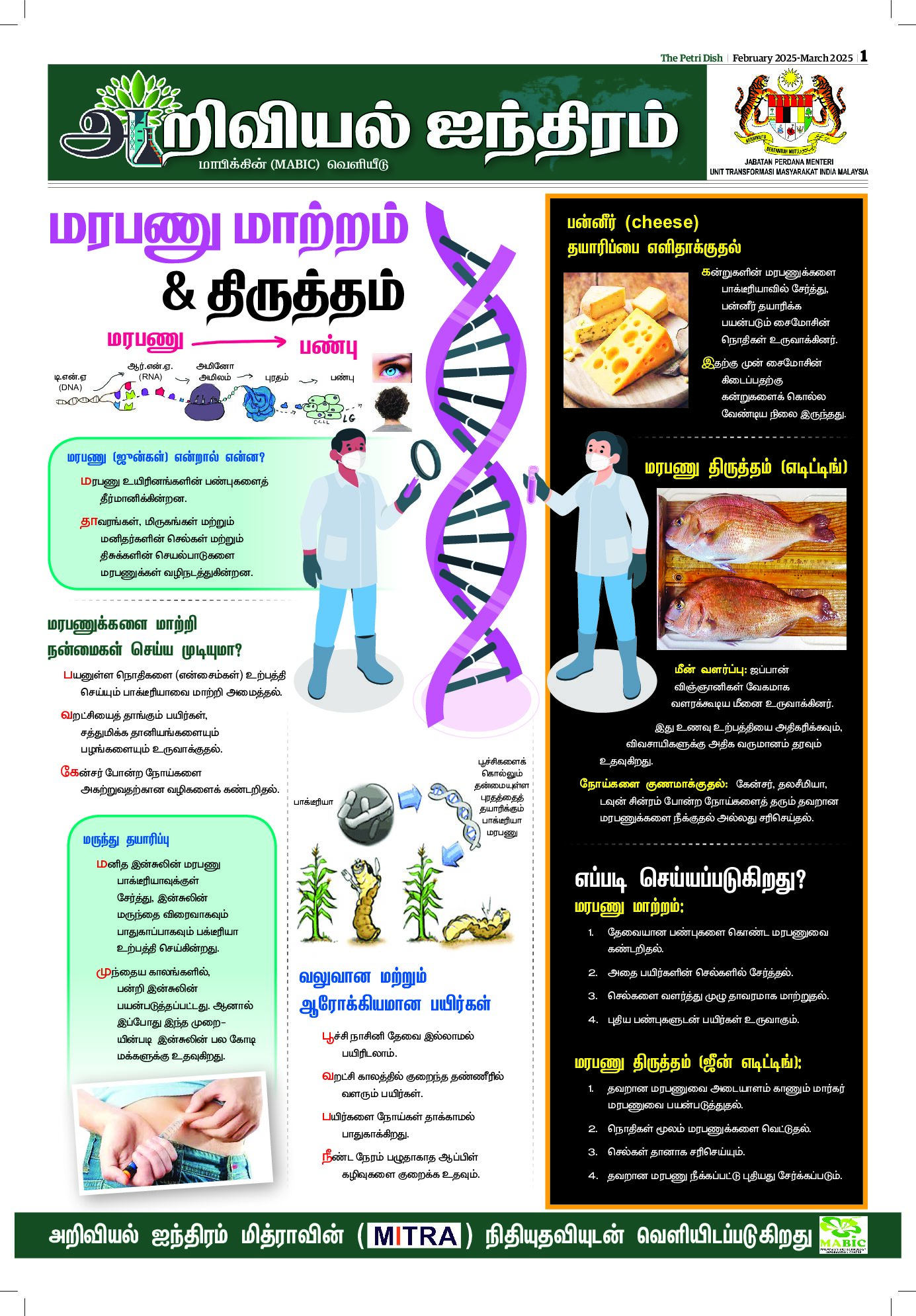

GENETIC engineering is most often linked to the foods that we eat and crops that we grow. It’s a technology that has generated a great deal of controversy, with opponents claiming it is inherently dangerous to human health and the environment. There is however no scientific evidence to validate those concerns.

GE foods have been exhaustively tested and researched with more than 2,000 studies vouching for their safety. All the major National Academy of Sciences in the world have concluded that they are no more dangerous than conventionally and organically grown crops. Not one incident of harm or allergic reaction has been traced to the consumption of GE foods.

What’s not widely known is that genetic engineering plays a critical role in the development and production of drugs that improve the quality of life for people with chronic diseases. For instance, virtually all of the insulin produced for diabetics is made through a process that involves genetic engineering.

Treatments for infertility, hemophilia, blood clotting and dwarfism also depend heavily on genetic engineering as does immunotherapy for developing treatments for cancer.

An article in the New Republic entitled, “GMOs Could Save Your Life – They Might Have Already,” highlighted the importance of genetic engineering in the manufacturing of essential medicines:

Consumers are used to hearing about GMOs in food crops, but may be unaware of the vital role GMOs play in medicine. Most modern biomedical advances, especially the vaccines used to eradicate disease and protect against pandemics…rely on the same molecular biology tools that are used to create genetically modified organisms…Consumers who scrupulously avoid genetically modified foods might be surprised to know that lots of drugs and vaccines they rely on are the product of GMOs.

In 2014, 10 of the top 25 best-selling drugs were biologics – drugs made up of recombinantly produced proteins – including blockbuster treatments for arthritis, cancer and diabetes. Of the 10 vaccines that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends for newborns, three are available in recombinant form.

One of the most promising uses of GE in medicine is in the development of vaccines. The Human Papilloma Virus vaccine was developed through a process involving genetic engineering. It gives protection against the various cancers — cervical, anal, throat and vaginal — that are caused by the virus. In December 2015, the FDA approved the first flu vaccine created with genetically modified materials.

Work is being conducted on developing a GM malaria vaccine and a GM Hepatitis B oral vaccine. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, a vaccine was developed by genetically modifying the tobacco plant and in June 2016, a GM vaccine was approved for human trials against the Zika virus. A genetically engineered AIDs vaccine began trials in southern Africa on November 30, 2017 which will last until 2021.

GE medical research my offer dramatic advances in cancer therapy. Last July, the FDA unanimously recommended the first such treatment for cancer patients. The FDA recommended approval of a treatment developed by Novartis that “genetically alters a patient’s own cells to fight cancer, transforming them into what scientists call a living drug that powerfully bolsters the immune system to shut down the disease.” The treatment is for a type of Leukemia.

In October, the FDA approved a second gene-editing treatment for cancer. It was for adults with an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (blood cancer). In the trials for the treatment which was developed by Kite Pharmaceutical, 54 percent of those participating had complete remission and 28 percent had partial remissions.

Gene therapy is advancing dramatically, noted Denise Grady of the New York Times: “Companies and universities are racing to develop these new therapies, which re-engineer and turbocharge millions of a patient’s own immune cells, turning them into cancer killers that researchers call a living drug. This has been utterly transformative in blood cancers,” said Dr Stephen Grupp, director of cancer immunotherapy at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

In December, the FDA approved the first gene therapy treatment for an inherited disease. It was developed by Spark Therapeutics and is designed to treat a rare inherited condition that causes a progressive form of blindness starting in childhood. In a study involving 29 patients ranging in age from 4 to 44, the treatment was demonstrated to be safe and effective with more than 90 percent of those participating showing at least some signs of improvement.

Albert Maguire, a professor of ophthalmology who led the study, which was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania, said many of the participants in the study went “from being legally blind to not being legally blind…What I saw in the clinic was remarkable.”

There were no side effects associated with the treatment, which involves injecting particles of a copy of a normally functioning gene into the back of each eye.

In a pioneering experiment, scientists at the Oregon Health and Science University in collaboration with colleagues in California, China and Korea were the first to edit the genes of human embryos, a process that could one day help prevent parents from passing along inherited diseases to their children.

The experiment involved repairing dozens of embryos, fixing a mutation which causes a heart condition that could lead to death later in life. Such treatments were given a vote of confidence last year, when the National Academy of Sciences indicated that altering the genes of embryos might be allowed under strict criteria if the objective is to prevent serious diseases.

According to the Times’ Pam Belluck, “The research marks a major milestone and, while a long way from clinical use, it raises prospect that gene editing may one day protect babies from a variety of hereditary conditions…”

Potentially, it could apply to any of more than 10,000 conditions caused by specific inherited mutations. Researchers and experts said those might include breast and ovarian cancer linked to BRCA mutations, as well as diseases like Huntington’s, Tay Sachs, beta thalassemia and even sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis or some cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Commenting on the experiment, Dr Eric Topol, the Director of the Scripps Translational Science Institute in La Jolla, California, noted that gene editing of embryos was “an unstoppable, inevitable science, and this is more proof it can be done.”

Some research regarding GE appears to border in the realm of science fiction. But if successful, it will have a great impact on treating diseases and expanding life expectancy. On August 10, 2017, for example, the journal Nature reported the results of an experiment in which researchers at Harvard and eGenesis, a private company, created gene-edited piglets that did not contain viruses that might cause diseases in humans. This might make it possible one day to transplant livers, hearts and other organs from pigs into humans.

David Klassen, chief medical officer at the United Network for Organ Sharing, a private, nonprofit organisation that manages the nation’s transplant system, said if pig organs were shown to be safe and effective, “they could be a real game changer.”

Other novel experiments being conducted and uses of gene editing include:

Biotechnology company Editas Medicine is using CRISPR technology to develop treatments for a rare, inherited retinal degenerative disease that appears in childhood and results in blindness.

Genetically engineered T-Cells may be used to develop new treatments for HIV and autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Researchers at Stanford University have used genetically engineered yeast to produce opioids for pain relief.

Synthetic Biologists at the Imperial College of London have genetically engineered yeast cells to produce penicillin. In laboratory experiments, they were able to demonstrate the GE yeast had antibacterial properties against streptococcus bacteria. Dr Tom Ellis of the Center for Synthetic Biology at Imperial College said:

“The rise of drug-resistant superbugs has brought a real urgency to our search for new antibiotics. Our experiment show that yeast can be engineered to produce a well-known antibiotic. This opens up the possibility of using yeast to…develop a new generation of antibiotics and anti-inflammatories.”

Scientists are working on putting vaccines in crops via genetic engineering. This would save the cost of transporting and refrigerating vaccines in developing countries.

Scientists at UC Davis are working on goats that produce milk protective against juvenile diarrhea, a major killer of infants in developing countries.

As New Scientist has noted, the potential benefits from gene editing are immeasurable. Promising results from animal studies targeting the liver, muscles and the brain suggest CRISPR genome-editing method could revolutionise medicine, allowing us to treat or even cure a huge range of disorders.

NOTE: Steven E. Cerier is a freelance international economist and a frequent contributor to the Genetic Literacy Project. : This is the third in a four-part series examining genetic engineering’s impact on our lives. Original article can be accessed at https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2018/02/07/gene-editing-revolution-medicine/