BY LAUREN SCRUDATO

An innovative “bio-bag” system developed by a team of doctors from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) mimics the environment of a mother’s womb and could provide the physiologic support premature babies need to properly develop.

One in ten babies born in the US are considered premature (younger than 37 weeks gestational age). Additionally, 30,000 births per year are critically preterm (younger than 26 weeks). Extreme prematurity accounts for one-third of all infant deaths and one-half of all cerebral palsy cases.

A child born at 22 to 23 weeks of gestation typically weighs about one pound–the equivalent of a full 16-ounce water bottle–and face a survival rate of 30 to 50 per cent. Infants that do survive can still face lifelong disabilities or abnormal organ development.

But even just a couple extra weeks in a mother’s womb can dramatically improve a premature baby’s outcome. This is what inspired a team of experts from CHOP to create an environment that replicates all aspects of normal fetal life to encourage natural growth and development of premature infants.

The artificial womb environment reported in the journal Nature Communications is the result of nearly four years of research and just as many prototypes. The study authors report that the latest version of the “womb” system successfully kept fetal lambs alive for up to four weeks – demonstrating strong promise that the system could be implemented in neonatal care units of hospitals for human babies.

“Our system could prevent the severe morbidity suffered by extremely premature infants by potentially offering a medical technology that does not currently exist,” said study leader Alan W. Flake, fetal surgeon and director of the Center for Fetal Research in the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment at CHOP.

The study authors conducted trials on fetal lambs because the animal’s prenatal lung development is similar to that occurring in humans.

The gestational age of the animals was equivalent to a human fetus at 22 to 23 weeks, which is considered the earliest a human baby could survive outside the womb if born prematurely. Eight of the fetal lambs survived for four weeks in the environment and continued to develop normally.

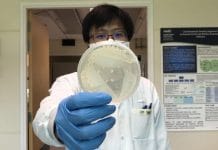

The first prototype was quite primitive, including parts of the system that were acquired from hardware stores. But years of trial-and-error and design tweaks have evolved to the current system, which is a sterile, temperature-controlled plastic bag filled with amniotic fluid created in the lab. Electronic monitors outside the “biobag” measure vital signs, blood flow and other critical functions.

The team noted that they can currently make more than 300 gallons of the artificial amniotic fluid per day, which is mostly made up of water and several different salts.

The artificial environment would be most beneficial for babies born at 23 to 28 weeks, to help “bridge the rough patch when they’re really struggling” to when they can thrive on their own, according to Emily Patridge, MD, researcher at CHOP.

As Flake explained in an educational video, the system works through two major components. The first is a circulatory system that connects the umbilical cord to an oxygenator powered via the fetuses’ own heartbeat. The baby’s heart pumps blood through the umbilical cord into the external oxygenator, which acts as the mother’s placenta to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide.

The other unique component of the system is the fluid environment that allows the fetus to swallow and breathe amniotic fluid like they naturally would inside the mother’s womb.

These components offer crucial advantages over traditional NICU methods such as incubators and ventilators.

Incubators isolate premature babies from bacteria and germs while outside the womb, and keep the babies warm, but are limited in offering any other supportive processes. Ventilators can cause lungs to develop abnormally, or even cause injuries that lead to lifelong conditions.

“Fetal lungs are designed to function in fluid, and we simulate that environment here, allowing the lungs and other organs to develop, while supplying nutrients and growth factors,” said Fetal Physiologist Marcus G. Davey, who designed and redesigned the system’s inflow and outflow apparatus.

“This system is potentially far superior to what hospitals can currently do for a 23-week-old baby born at the cusp of viability. This could establish a new standard of care for this subset of extremely premature infants,” added Flake.

Flake believes clinical testing at neonatal wards could happen within the next few years, and future versions of the system would be redesigned to look more like traditional incubators, as opposed to the current bag-like design.

Flake and fellow study authors did address potential ethical concerns associated with the system, and determined that they do not intend to ever use the system as a way to extend limits of viability. For example, Flake said he would be “very concerned” if a doctor used this device to rescue infants born earlier than 22 weeks because the system could actually inflict harm at that early of a stage in development.

As the study authors note, there are still some physiological aspects and development that only a mother can provide to her fetus, so attempting to use the device earlier than 22 weeks would impose high risks. — Laboratory Equipment