A research team led by the University of Minnesota, has discovered a groundbreaking process to successfully rewarm large-scale animal heart valves and blood vessels preserved at very low temperatures. The discovery is a major step forward in saving millions of human lives by increasing the availability of organs and tissues for transplantation through the establishment of tissue and organ banks.

The research was recently published in Science Translational Medicine.

The University of Minnesota holds two patents related to this discovery.

“This is the first time that anyone has been able to scale up to a larger biological system and demonstrate successful, fast, and uniform warming hundreds of degrees Celsius per minute of preserved tissue without damaging the tissue,” said John Bischof, University of Minnesota mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering professor, and senior author of the study.

Bischof said in the past, researchers were only able to show success at about one milliliter of tissue and solution. This study scales up to 50 milliliters, which means there is a strong possibility they could scale up to even larger systems, like organs.

Currently, more than 60 per cent of the hearts and lungs donated for transplantation must be discarded each year because these tissues cannot be kept on ice for longer than four hours. According to recent estimates, if only half of unused organs were successfully transplanted, transplant waiting lists could be eliminated within two years.

Long-term preservation methods, like vitrification, that cool biological samples to an ice-free glassy state using very low temperatures between -160 and -196 degrees Celsius have been around for decades. However, the biggest problem has been with the rewarming. Tissues often suffer major damage during the rewarming process making them unusable, especially at larger scales.

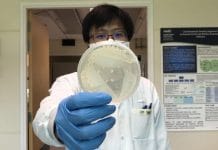

In this new study, the researchers addressed this rewarming problem by developing a revolutionary new method using silica-coated iron oxide nanoparticles dispersed throughout a cryoprotectant solution that included the tissue. The iron oxide nanoparticles act as tiny heaters around the tissue when they are activated using noninvasive electromagnetic waves to rapidly and uniformly warm tissue at rates of 100 to 200 degrees Celsius per minute, 10 to 100 times faster than previous methods.

After rewarming and testing for viability, the results showed that none of the tissues displayed signs of harm, unlike control samples rewarmed slowly over ice or those using convection warming. The researchers were also able to successfully wash away the iron oxide nanoparticles from the sample following the warming.

Bischof said the discovery is the result of his team’s research in many different fields to preserve or destroy cells and tissue at either ultra high temperatures or ultra low temperatures.

“We’ve gone to the limits of what we can do at very high temperatures and very low temperatures in these different areas,” Bischof said.

“Usually when you go to the limits, you end up finding out something new and interesting. These results are very exciting and could have a huge societal benefit if we could someday bank organs for transplant.”

Although scaling up the system to accommodate entire organs will require further optimisation, the authors are optimistic. They plan to start with rodent organs (such as rat and rabbit) and then scale up to pig organs and then, hopefully, human organs.

The technology might also be applied beyond cryogenics, including delivering lethal pulses of heat to cancer cells.